From our Archive: Bob Gilmore 'How I Listen'

5th May 2021

Features NMC RecordingsThe late Bob Gilmore shares his thoughts on listening, in this article originally published in our Friends Newsletter in 2014. Alongside articles like this, our quarterly Friends Newsletter is packed with behind-the-scenes updates on recordings and education projects, as well as invitations to see our work in action plus opportunities to meet composers and artists; find out more about becoming a Friend here.

It may be a truism to say that each of us listens to music in our own way, but it is inescapably the case. No one starts from a blank slate: we are all conditioned by numerous factors including taste, upbringing, musical education or lack thereof, age, nationality, sexual orientation (discuss), and much more. This is only normal, and as it should be. But until recently the manifold implications of this have received little attention in the critical writing about music.

Music psychologists have long studied the mechanisms of hearing and perception but (with some honourable exceptions) have paid scant regard to genuinely new music. And only very recently has the idea of a “history of listening” become a real subject within musicology. A research project entitled The Listening Experience Database (LED), currently underway as a joint project of the Open University and the Royal College of Music, is attempting to build an expandable database of records of the “private and intimate” listening experience: we wish them well.

I have been reflecting on how I myself listen to music. Within the context described above I can justify this not so much as an exercise in narcissism but as a form of proto- (or, more likely, pseudo-) research. The question is hugely complex: beyond the already knotty problems of perception we must take into account the ever-shifting sands of cognition, of understanding. I “hear” Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony differently now than I did when I first made its acquaintance more than forty years ago, partly as a consequence of the many different interpretations I’ve experienced in the meantime, but also, more crucially, because my sense of what music is has expanded so much since my youth. The encounter with twentieth- and twenty-first century music has long since eroded the sense I once had of the normativity of Beethoven’s language: the present, as always, influences our perception of the past.

Specifically, though, I am more interested in the basic ways I (and others) listen to music - listening in an intuitive, rather than intellectually mediated, sense. Some people like a tune, some crave rhythm, some enjoy colours, some want “emotions”, and so on. My own primary way of listening, the one that gives me the most satisfaction, has to do with harmony. It is the nature of the harmony that most attracts me to a piece of music, or puts me off it. By that I don’t mean that the harmony need necessarily be complex: sometimes one chord is enough. I also don’t mean that I can’t enjoy music that operates on a wholly different basis - music for untuned percussion, say. It’s simply that, finally, harmony is the aspect of music that most entices me, convinces me, that most fully engages my heart and my brain in the experience of listening.

I wonder if we are “better” listeners now than we were in the nineteenth century. Clearly, we hear far more music today than at any earlier period in history, but that doesn’t mean we listen more, or more intelligently. If anything, we suffer from the problem of overload, of too much choice - from a promiscuity of information, from the proliferation of contemporary sounds, styles and aesthetics. I doubt that this overload has improved matters. I would argue that over the past half-century or more we have witnessed the growth of the opposite phenomenon, a troubling one: a deterioration in our listening skills. To have a vibrant new music culture that evolves in interesting ways we need not merely good playing and composing skills, but also, crucially, composers, performers and musicologists with the ability to hear clearly and accurately. I believe that of all the parameters of music it is harmony that has taken the hardest knocks in this situation.

The deterioration in our listening skills first became a real problem with respect to non-tonal music. Simply put, it is more difficult to hear wrong notes in Schoenberg than in Haydn, both when one is playing and when one is listening. There are numerous reasons for this. One is that Haydn’s music speaks a language that is extremely familiar to us, for all his characteristic development of it, whereas it might be said, exaggerating slightly, that every post-tonal composer is post-tonal in his/her own way. Schoenberg’s music also springs from a general language - diatonicism and tonality-conscious chromaticism - but his departures from it are highly personal. His music has lived on, albeit in relative obscurity, because those departures seem persuasive to us - or at least some of them do.

In post-tonal music - whether that music is “atonal”, serial, “free”, or based on personal systems of interval relations specific to a particular composer or even a particular piece - it can be hard to judge wrong notes not merely aurally but also, at times, conceptually. More than forty years ago the musicologist Hans Keller argued that, even though “a rich variety of replacements for tonal organisation has been discovered in [the twentieth] century”, nonetheless “harmonically, none makes sense unless it audibly contradicts that which it replaces; and it is, ultimately, in terms of these contradictions that notes are heard as right, however difficult the task may, at times, appear to be”. Is his argument still valid today?

Thinking of more recent music - some experimental music, say, or free improvisation - we may well ask what counts as a wrong note in an aleatoric situation where sounds collide accidentally without pre-planning, harmonic or otherwise. (Here a “wrong note” means a harmonically and/or melodically inexplicable choice, not the “classical” sense of something different than is written in the score; this kind of music will often not have a score, at least not a conventional one.) In these contexts, is the concept of a wrong note still meaningful? Arguably, no: the distinction between right and wrong notes here becomes irrelevant. This is fine as long as we can then accept the fact that the resulting music is, in this specific sense, incomprehensible - and not just incomprehensible with regard to the laws of modal/tonal music, however broadly defined, but incomprehensible in the sense of deliberately declining to propose any new form of aurally intelligible harmonic logic. We could of course say that, in such music, other parameters have replaced vertical listening as the main dish: rhythm, timbre, texture, “gesture”, and so on, and that we should be content with that - why should harmonic relations be dominant, anyway? Well, perhaps not necessarily “dominant”, but I can suggest one compelling argument in favour of their continued importance, one that the American composer Ben Johnston expressed many decades ago: that harmonic listening is simply “too basic a parameter to be allowed to fall into disuse”. With a lack of concern for harmony other musical values bite the dust too, such as a careful approach to intonation; one cannot play really in tune if one cannot predict the pitches one is supposed to tune to. (Good intonation presupposes a form of inner pre-hearing of a pitch or pitches immediately ahead in the music, a fascinating but little discussed aspect of good performance practice.)

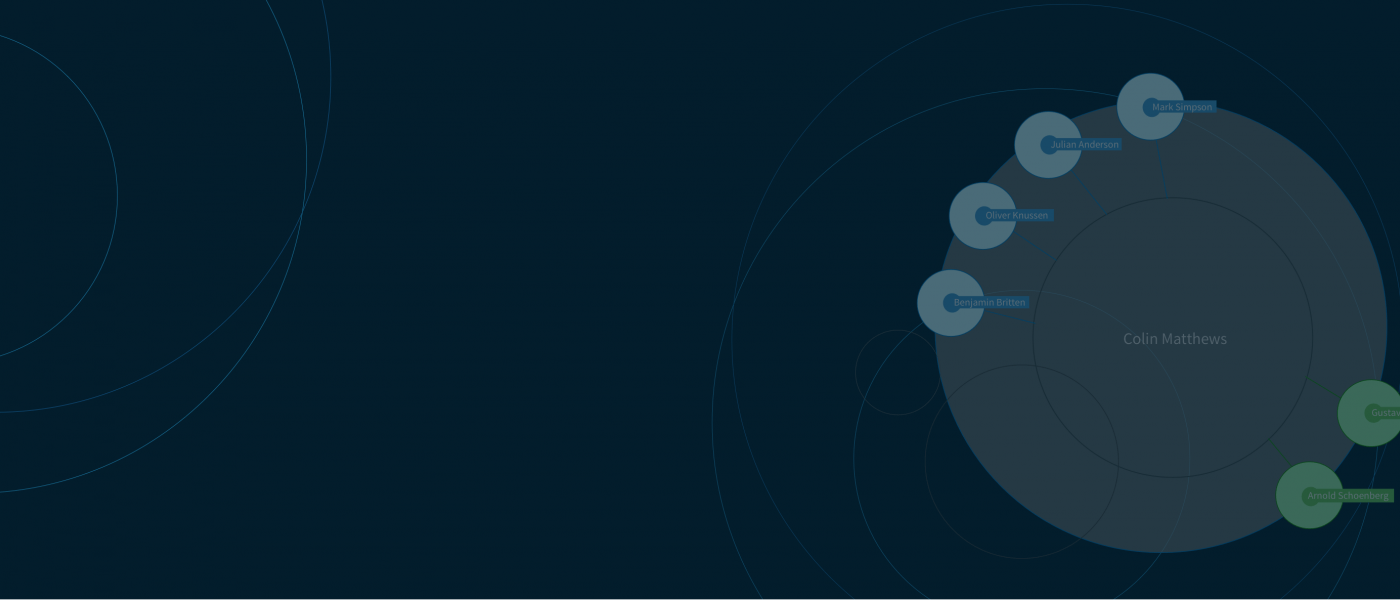

One example of a new approach to harmony that is very much concerned with aural intelligibility, and with tuning, is to be found in the “spectral music” that originated in the Parisian new music scene of the 1970s. (The term is in scare quotes for the reason that not one of its leading practitioners accepts its validity as a descriptive term for what they do.) This approach has evolved in the music of subsequent decades, and informs the harmonic language of such recent works as Julian Anderson’s Eden (NMC D121) or Donnacha Dennehy’s Bulb (NMC D147). In contrast, it seems to me that quite a lot of new music today exhibits what composer Roberto Gerhard memorably called “pitch fatigue”: “at long last”, he wrote in the late 1960s, “‘atonality’, in the literal meaning of the word, has become a stark fact in our day and age, owing to [this] puzzling phenomenon”. Of course, few composers will admit that they don’t care about pitch, or are bored of it; and, sometimes, repeated listenings to an apparently impenetrable piece will begin to reveal a form of harmonic logic that was not immediately evident. And there is a lot of music in which what happens on other levels is so compelling that our listening mode shifts accordingly. I greatly enjoy listening to Jonathan Harvey’s Bird Concerto with Pianosong (NMC D177) or to Richard Barrett’s Dark Matter (NMC D183), even though much of the time I draw a blank at what’s going on harmonically (without, it must be said, having studied the score of either piece).

The difficulty of hearing wrong notes in post-tonal music, and the irrelevance of the concept of a wrong note in most forms of aleatoric music or free improvisation, has made some listeners sharpen their listening skills in a different way so they can navigate these new musical contexts with some confidence - contexts in which the presence of a clear harmonic superstructure would be an irrelevance or an anachronism. But I suspect many listeners - perhaps even the majority - experience something closer to what I experience: the harmonic incomprehensibility, or semi-comprehensibility, of some new music, where I can’t fathom the logic of pitch choice even after several attempts, only dulls my perception. Frustrated in the attempt to understand the music harmonically, I slip into more passive, less demanding modes of listening, letting the music do its thing and abandoning the difficult task of really trying to follow it. Is this a problem? Maybe not, if the music is still enjoyable to listen to. But it seems to me that in such circumstances what I experience is a form of mental laziness, akin to giving up the struggle to follow an intricate philosophical text and simply admiring the choice of font or enjoying the smell of the pages in the book. Some people may well be content to listen to music in this way; but they belong to a club that would probably not accept me as a member.

NMC's Discover platform is created in partnership with ISM Trust.